“A Magical Combination”

|

|||||

“IF A REAL VACATION is sought amid the beauties of primeval landscape and forest, where the heart finds nature ever in a responsive mood, and where rest and restored nerves are the reward of your selection, then we urge you to seek Billie Bear.”

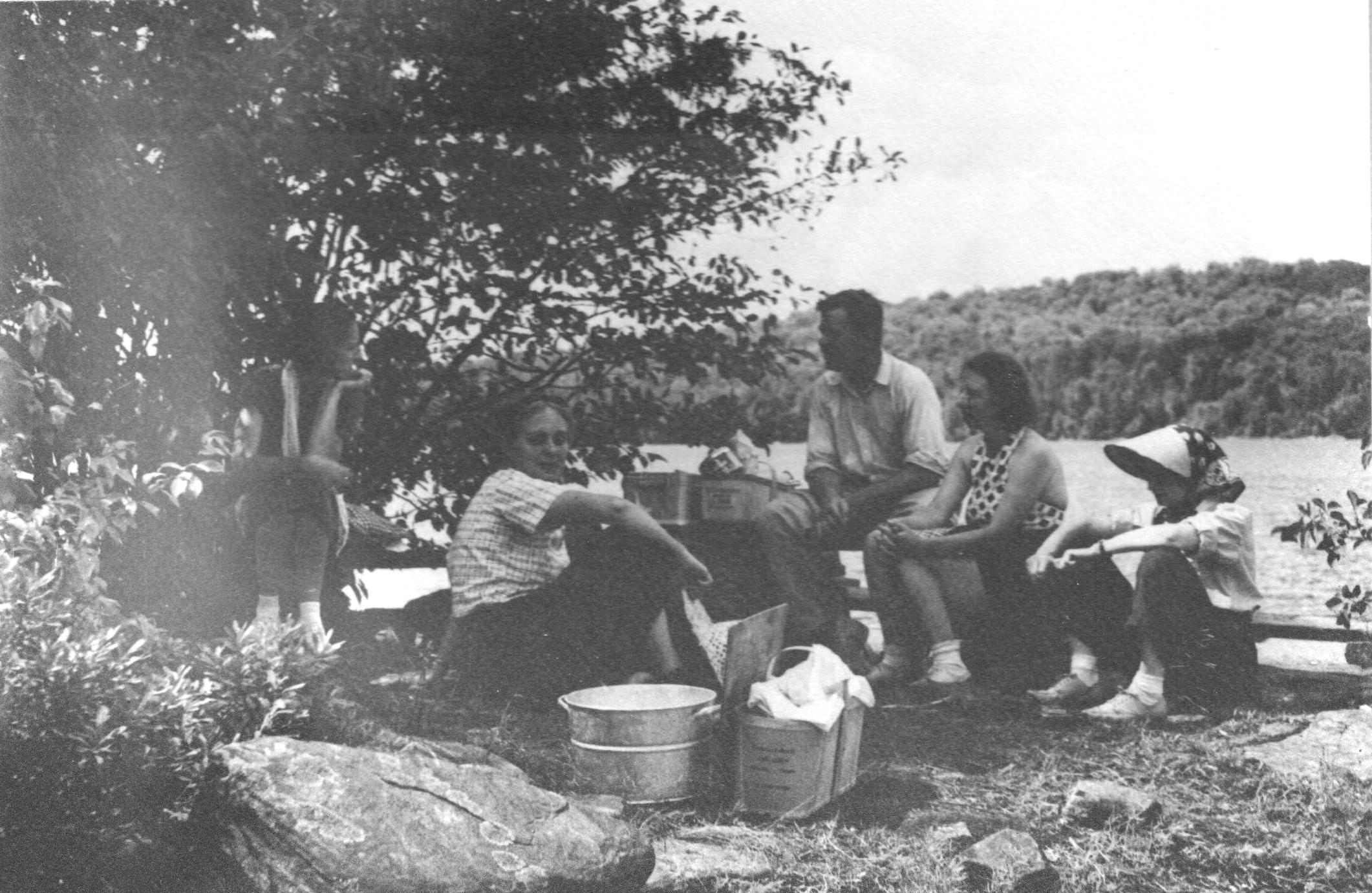

“WE ALWAYS put the heat on on cold mornings and raced down the rocky hill – to plunge into Bella [Lake]. The quiet, the hemlocks, dark against the rising mist on the lake, the silver-blue water – unforgettable!”

|

|||||

|

|||||

THE IDEA of beauty in a nature that was wild and unpredictable, as opposed to cultivated and orderly, emerged with the Romantic era of the early nineteenth century. The thirst to experience “unspoiled” natural surroundings was fuelled also by the increasingly industrial urban environment. City-dwellers of the upper and middle classes, with the means and time to take an annual vacation, sought respite and renewal in wilderness – or, at least, in their perception of what authentic wilderness might be. Muskoka was within reach of Toronto and northeastern American cities, and its rock, waterfalls, and sparkling lakes provided plenty of opportunities for vacationers to encounter a natural and wild landscape on their own terms. Picturesque scenes abounded, and the various hotels, tourist homes, and camps offered a choice of experiences. |

|||||

|

|||||

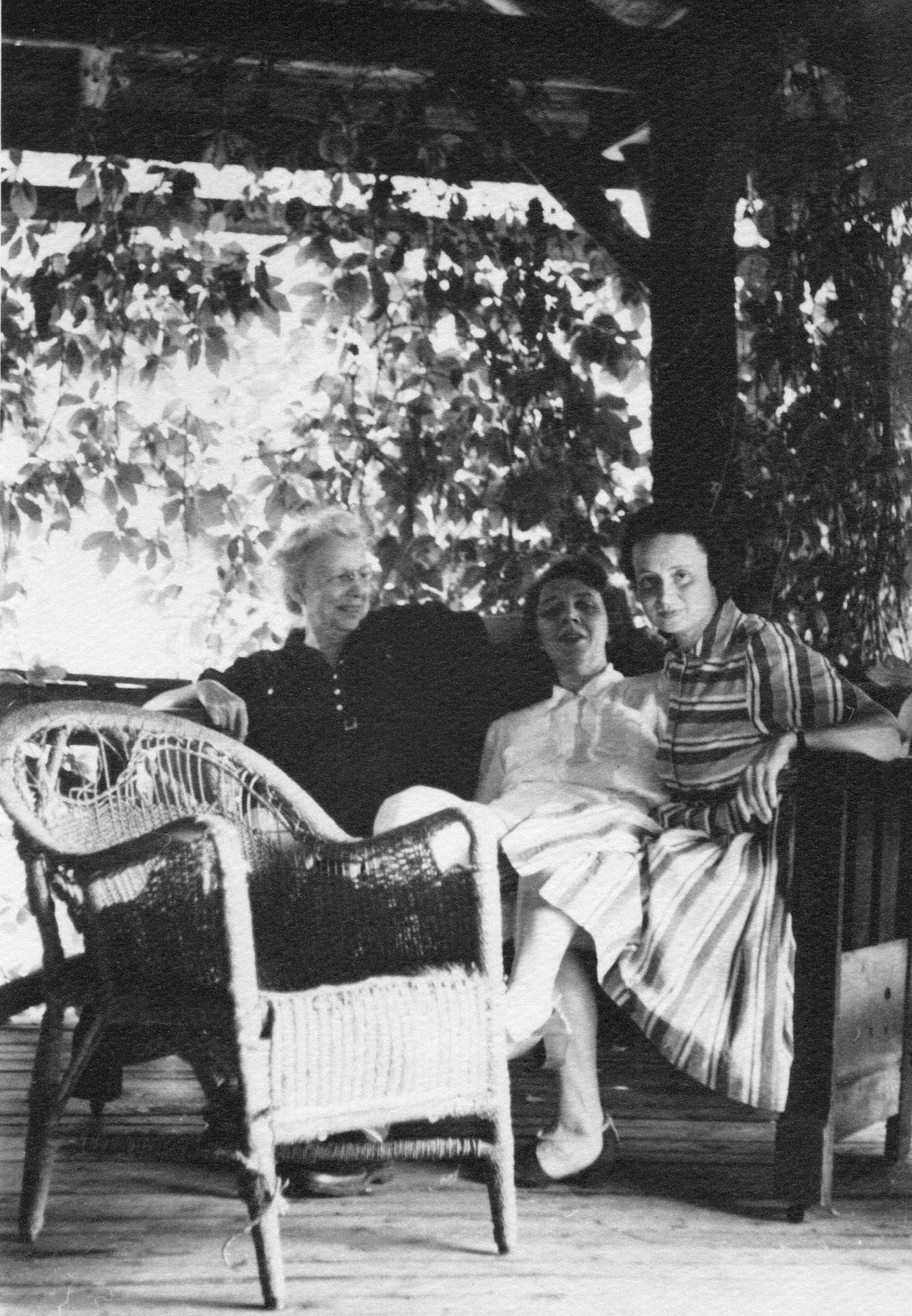

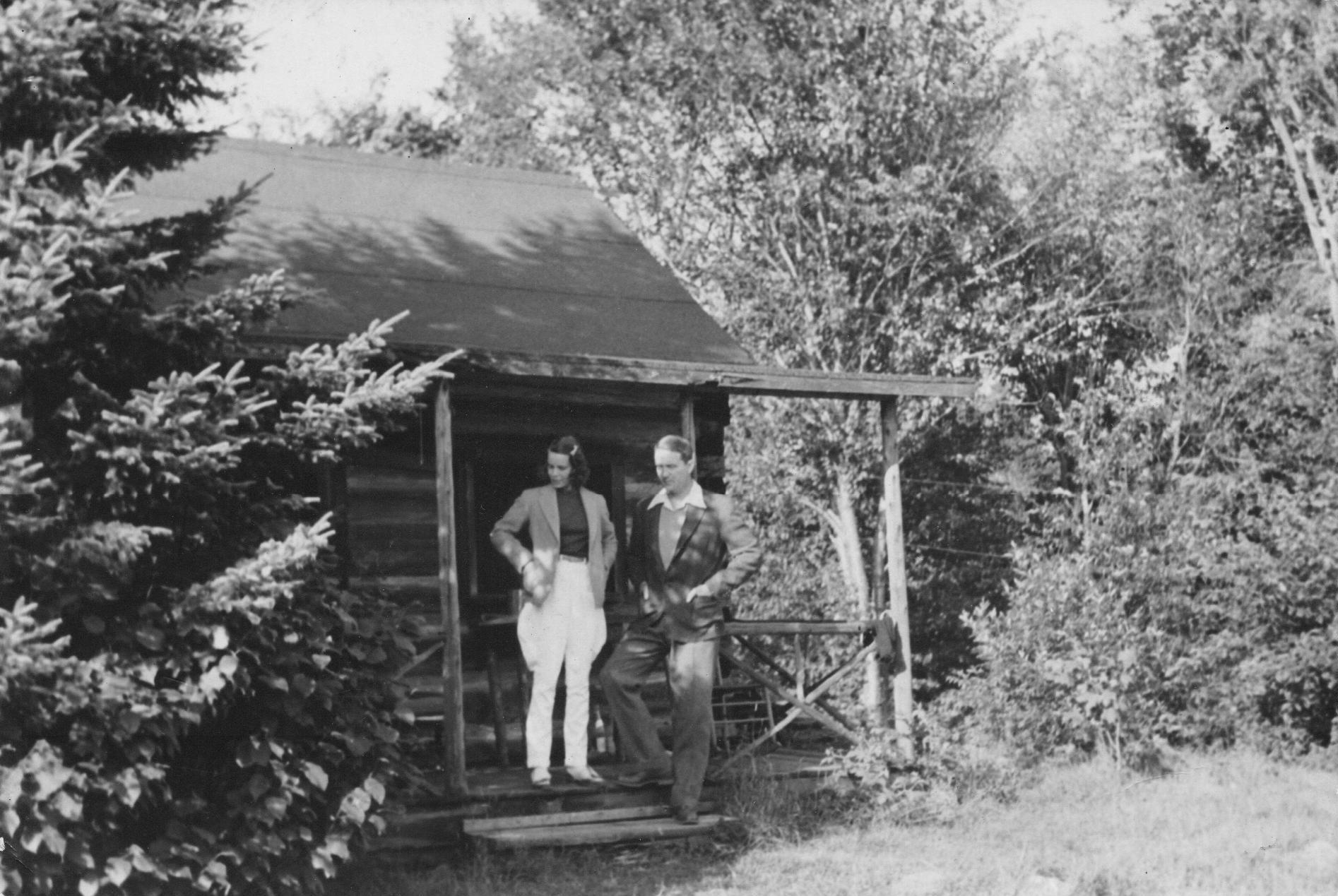

| Georgian Bay and Algonquin Park developed a particular cachet thanks to a group of Toronto artists experimenting with their vision of the rugged landscape. Painter Tom Thomson epitomized the bush experience as part of the Canadian character, a representation that grew to mythical proportions after his death. Although no corroboration exists, a story persists that Thomson had reserved a cabin at Camp Billie Bear for his honeymoon in 1917. If the engagement was ever made, Thomson did not keep it, as he drowned in Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park in July of that year. A contemporary who did later reach Bella Lake was Group of Seven member A. Y. Jackson, a friend of the Stewart family, whose cottage was on Georgian Bay. Jackson visited Jean [Stewart] Dowsett on several occasions during the mid-1950s. | |||||

|

|||||

Anti-modern sentiment among well-to-do urban dwellers in the early twentieth century brought an uncomfortable feeling about how easy life had become and invoked a desire for authentic adventure away from the growing comforts and conveniences of home. Early guests to Camp Billie Bear – both American and Canadian – certainly were influenced by this anti-modernism, and it was fanned by the advertising rhetoric of the Grand Trunk Railway and individual tourist camps and hotels. The availability of automobiles in the 1920s helped make travel more widely accessible, and by the 1930s most Billie Bear guests were arriving by car. Although campgrounds became popular with the advent of the motor car, so did more comfortable facilities. As comments from the 1940s reveal, while guests still relished the thrill of “roughing it,” they could sometimes be surprised that nature set its own terms. |

|||||

|

|||||

“FIRST YEAR [1940] we had Pell house attic for my husband and 5-year-old son, a cabin on road out for my daughter and me. Our first night was horrendous! I heard bumps on the porch – clawing at the screen. Drunken lumbermen, I th[ought] – I stole over, shut and locked doors and windows – shook violently and crawled wild eyed into bed. Porcupine tracks on the porch were the answer next day!”

“I REMEMBER one early [trip to] 2nd Sandy when Nick and I walked home and my seven-year-old daughter and husband paddled. Nick and I ran thr[ough] the woods singing loudly – every stir of leaf could have been a BEAR!!

|

|||||

|

|||||

Sources |

|||||

Barrett, Peter, “Muskoka Tourism,” Huntsville Public Library, file “Tourism – Muskoka (District Municipality),” summer 1984. Billie Bear Documents Archive, Camp Billie Bear brochures, 1930s; Gerry Livingston letter to Barbara Paterson, August 1982. Cameron, Ross D., “Tom Thomson, Antimodernism, and the Ideal of Manhood,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, vol. 10, no. 1 (1999), pp. 185-208. Dowsett, Bill, conversations 2004 and 2005. Hart, E. J., The Selling of Canada: The CPR and the Beginnings of Canadian Tourism (Banff: Altitude Publishing Ltd., 1983). Huntsville Forester, “Huntsville as a Future Tourist Resort,” August 11, 1910, p. 1; “All Lake of Bays Preparing for the Summer Rush,” May 22, 1924, p. 1; “Neat Booklets Issued,” June 3, 1926, p. 1. Jasen, Patricia, Wild Things: Nature, Culture, and Tourism in Ontario, 1790-1914 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995). “Lake of Bays, Highlands of Ontario,” Grand Trunk Railway System pamphlet, c. 1915, https://archive.org/details/lakeofbayshighla00gan/mode/2up

Shifflett, Geoffrey, “The Evolving Muskoka Vacation Experience, 1860-1945” (PhD thesis, Department of Geography, University of Waterloo, 2012), http://hdl.handle.net/10012/6916

Wall, Sharon, “Antimodernism,” chapter 10.3 in John Douglas Belshaw, Canadian History: Post-Confederation, BCcampus Open Education, https://opentextbc.ca/postconfederation/chapter/10-3-antimodernism/ |

|||||